Dr. Steven Hail is an economics lecturer at the University of Adelaide in Australia.

This blog post is a summary of two videos (a part 1 and a part 2) of a talk he gave to a group named Modern Money Australia, on the 23rd of June 2019 on the topic of money and finance. Specifically how the central bank and federal debt shapes the economy.

As he lives, teaches, and gave this talk in Australia, he uses the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Australian federal debt as his examples when talking about money and finance, but the principles apply to any nation with a sovereign currency.

This post is a summary, not a word-for-word transcript, for people who want to understand the core of what he said, without watching the entire two videos which together run for an hour and twenty minutes.

However, for those who do wish to watch the videos (as they contain more than my fairly terse summary), they’re below.

Table of Contents

Modern Monetary Theory is built on the work of prior economists

Most important among them were Abba Lerner, Wynne Godley, and Hyman Minsky.

Hyman Minsky’s ideas “came to fruition” so to say, after his death in 1996, and he’s much more famous among economists now than he was when he lived.

A failure of progressive politics is to have NEVER understood how the monetary system works

He states this as his opinion, not a fact, although it’s a reasonable and credible opinion based on my experience.

Not understanding how money and finance works have caused or allowed an acceptance of neoclassical economics as to how monetary systems work.

In doing so, they failed to understand options that exist, but which they’re not seeing.

Money and finance basics consists of two axioms and one identity

Axiom: All economies face real constraints

In every society, there is a limited supply of labour and skills, capital equipment, technology, infrastructure, natural resources, and ecological space.

These real constraints limit our productive capacity.

If a currency-issuing government spends beyond these real-world constraints (i.e.: attempts to “activate” more resources than there are, you WILL have inflation, as the very act of doing so will bid up the price of the now scarce resources.

Axiom: Monetary sovereign governments face no purely financial constraints

If you are the monopoly issuer of a currency, you can not run out of that currency.

Identity: Sectoral balances sum to zero

This is a mathematical relationship that is true by definition.

For every lender in a financial system, there must be a borrower. For every buyer, there must be a seller. Every dollar spent by someone is a dollar of income to someone else.

The three sectors of an economy are:

- Currency Issuer (often called the Government sector)

- Domestic Currency Users (often called the Private sector)

- Foreign Currency Users (often called the Foreign sector)

Because they must net to zero, they can not all be running surplusses.

If two of those sectors are in surplus, the other MUST be in deficit, but an amount equal to the total surpluses of the other two.

If net exports is in surplus, and the Government is in surplus, whose in deficit?

When net exports are in surplus (the nation exports more than it imports) and the government is in surplus (they spend less than they take it), then by definition, the private sector (businesses, households, etc) MUST be in deficit. The only way this can occur is if the domestic currency users draw down savings and/or run up debts.

It’s spend and tax, not tax and spend

Monetary sovereign governments issue their own currency, use a floating exchange rate, and have no significant foreign currency debt.

The United States, Canada, Australia, the UK, China, Japan, etc, etc are monetarily sovereign. Germany, France, Greece, Portugal, Spain, etc, are not. As such, you can not equate them. From a monetary perspective, Greece has more in common with Alabama and New Brunswick than they do with the United States and Canada.

Currency users must obtain money before they can spend it, or run down savings, or run up debt.

Currency issues, being THE source of the currency, not only do not have that constraint but MUST spend into the economy in order for there to be money in the economy to tax back.

Currency issuer surplusses have to be financed

This is an interesting way to look at things, and most people have this idea exactly backwards.

If a currency issuer government is going to run a surplus, some other sector must run a deficit. That surplus has to be financed.

Currency issuer deficits are self-financed. When a currency-issuing government spends more into the economy than they tax back out, they’re increasing the money in the economy. No other sector has to “pay for it”.

Whereas currency issuer surpluses require deficits in at least one of the other sectors.

In order for an economy to grow long term, the currency issuer MUST run deficits and when the currency issuer runs a surplus, at least one of the other sectors MUST run a deficit.

Anyone can create money, but….

Hyman Minsky has been quoted as saying:

Anyone can create money. The problem lies in getting it accepted.

His point is any payment obligation can circulate within a community if the person who made the promise to pay is thought to be someone who will pay the obligation independent of who holds it.

If everyone knows me to be a good guy who always pays his debts, and I owe person A $100 for some reason, they can transfer the ability to collect that payment to person B in exchange for something. Person B can in turn transfer it to person C in exchange for something else, and so on. If that occurs, my promise to make the payment effectively serves the purpose of “money”.

Having said that, the odds of my IOU being accepted by others in exchange for goods and services are slim.

Commercial banks create money denominated in currency units

This sounds weird the first time, or maybe the first few times, you hear this, but there is a distinction between central bank-created currency, and commercial bank-created money, which is not currency but looks and acts like it, and for all practical purposes substitutes for it.

When you go to a bank and borrow money, if they believe you to be creditworthy and capable of paying back the loan, they will create a deposit for you in their bank where you will find the money you’re borrowing.

Where does the money you’re borrowing come from? It doesn’t “come from” anywhere. It simply appears in your account. The bank created it out of thin air when they funded the deposit.

Each of those dollars is an IOU that you’ve agreed to return to the bank later, over time, with interest.

And those IOUs, being denominated in the currency unit of the dollar, are accepted by anyone who accepts dollars.

How does the monetary system work?

The central bank operates under a charter provided by the nation’s lawmakers and has the independence to:

- Set and manage to a target interest rate

- Ensure that payments made between people who bank at different banks clear

Commercial banks also operate under government charters, in a franchise relationship (sort of) to the central bank.

Commercial banks maintain deposits at and borrow money from, the central bank. The federal government also banks at the central bank as do foreign central banks.

Businesses, non-federal governments, and individuals maintain deposits at and borrow money from, commercial banks.

While the relationship between the treasury and the central bank is very complex, I’m thinking this is intentional, perhaps to obscure the fact that when the central bank “loans” money to the treasury, it’s as if your right pocket loaned money to your left pocket. You’re still “loaning” money to yourself.

There is a thing called “the monetary base”

It’s all the banknotes and coins in circulation, as well as the banking reserves (exchange settlement accounts) the commercial banks keep on deposit at the central bank. This is the “currency” mentioned above.

It is the money the treasury spent into existence or the money the central bank loaned into existence, depending on your perspective. as those are two different aspects of the same thing.

The banknotes and coins are used by people to cover some day-to-day expenses, but the bulk of the monetary base is the “seed money” for the commercial banking system.

It’s the “banking reserves” the commercial banks keep on deposit at the central bank.

Your bank pays your taxes

I know you think YOU pay your taxes, and when you write a check or use a payment card to do so the bank does take your money. But the tax liability is actually paid by your bank using some of the reserves they have on deposit at the central bank.

Another use of banking reserves is processing payments for payments made between people and organizations who use different banks.

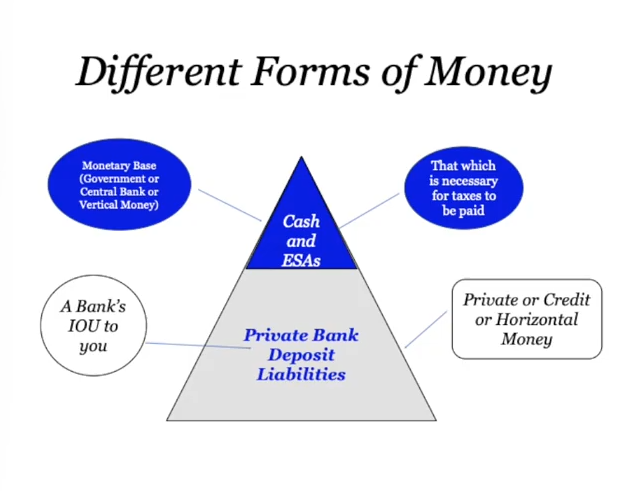

The different forms of money

The diagram below shows different forms of money that exist in a modern economy.

ESA: Exchange Settlement Accounts

These are the banking reserves that banks maintain in order to 1) provide customers with banknotes and coins, and 2) ensure that payments between customers of different banks clear. These banking reserves are “topped up” by the central bank as deemed necessary.

This is called verticle money because it’s “passed down” to the private sector.

It is a net financial asset to the private sector.

This is an important concept. Currency issuer deficits, create currency user surplusses. Currency issuer liabilities create currency user assets.

This verticle money represents 3% to 5% of the money in the money supply.

Private Bank Deposit Liabilities

These are liabilities to the bank, as any depositor can come in at any time and withdraw the money.

This is the money in our economy which is not currency, and yes I know that distinction seems irrelevant to us.

These are bank IOUs that have been issued to depositors in the form of loans.

Rember that when you borrow money from a commercial bank, they put that money into a deposit account for you.

This means that loans create deposits.

Now while the loan the bank made is an asset to the bank and a liability to the borrower, the deposits created by these loans are assets to the borrower and liabilities to the bank, hence they are bank IOUs.

This is called horizontal money because it’s “passed across” the private sector.

This represents 95% to 98% of the money in the money supply.

This horizontal money is literally created out of debt, and that debt needs to be repaid over time.

All money is debt, but not all debts are money

Vertical money (banking reserves or exchange settlement accounts) are necessary to pay taxes.

Horizontal money (bank-created credit money) is accepted because it can be CONVERTED into vertical money and then used to pay taxes.

Currency issuer debt is the net money supply.

Taxes drive money

In a very literal sense, taxes drive money.

Professor Hail explains this using an example from the British colonial period.

The British colonizer shows up, and they want the locals to work on a plantation.

So they impose a tax which the native population has to pay. And unless the native populations pay, they’ll be imprisoned.

But, the native population has none of the money they need to pay their taxes.

So how do they get some?

They get some in exchange for working on the plantation.

This is how taxes drive money.

This also means the acceptance of money, the value of money, is supported by the threat of state violence. Which it is.

But, it is not necessary for everyone to work on the plantation in order for everyone to pay their taxes.

This is because people who do get paid to work on the plantation need things, which others can sell to them, in exchange for some of that money.

Today, taxes reduce the money supply

There is such a thing as having too much money in circulation.

People with money buy things.

So an economy with more money tends to be an economy with more demand for goods and services, simply because more people can afford them.

If the demand for goods and services exceeds the productive capacity of the economy, the goods and services are by definition scarce (as demand exceeds supply) and scarcity creates inflation as people bid up the prices of goods and services.

One way of managing the amount of money in circulation is to use taxes to take some out.

Taxes are a way of reducing private sector demand. Sales of bonds by the currency-issuing government is another.

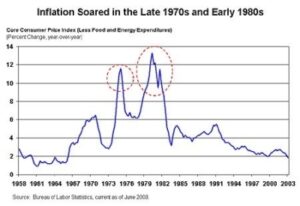

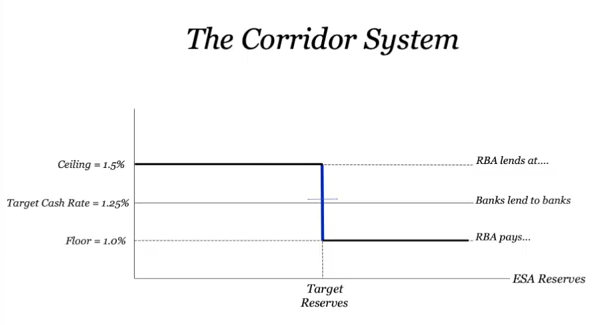

The central banks uses a “corridor system” to hit their target interest rate

This is obviously not a current example, as the current target interest rate (target cash rate) is 0.25% in the United States, 0.25% in Canada, and 0.10% in Australia.

It is also an Australian example, although the concepts apply in every other modern economy. The RBA is the Reserve Bank of Australia, but could just as well be the Federal Reserve Bank, the Bank of Canada, the Bank of Japan, the People’s Bank of China, etc.

The goal is to keep the interest rate at the target rate by taking action whenever the interest rate rises to the upper limit (the ceiling) or falls to the lower limit (the floor).

As stated above, banks need reserve balances. Not much, but some.

And sometimes a bank finds itself with more than it needs, and sometimes a bank finds itself with less. The central bank facilitates banks lending reserves to each other, and this corridor system is part of that overall mechanism.

If “too many” banks find themselves with excess reserves, there will be too much cash in the system.

When this happens, more banks want to lend reserves than want to borrow reserves. In other words, the supply of reserves exceeds the demand for reserves, and the cost of reserves (the rate of interest banks are willing to pay to borrow reserves) drops.

Alternatively, if too many banks find themselves short of reserves, there will be too little cash in the system.

When this happens, more banks want to borrow reserves than want to lend them. In other words, the demand for reserves exceed the supply of reserves, so the cost of reserves (the rate of interest banks are willing to pay) rises.

To hit the target interest rate, the central bank either removes reserves from the banking system or adds them to it.

Repos and reverse repos

They do this by making overnight loans to member banks or borrowing money from member banks, using Treasury securities as collateral.

These occur EVERY DAY. Sometimes twice in one day if the central banks feel a second adjustment is needed.

Repos remove reserves from the banking system

A repo is a repurchase agreement.

If the banking system has too many reserves, the central bank sells treasury securities to the banks that they agree to repurchase the next day. This looks the same as if the central bank took overnight loans FROM member banks.

Reverse repos add more

A reverse repo is a reverse repurchase agreement.

If the banking system needs more reserves, the central bank buys treasury securities from the banks that they agree to sell back (reverse repurchase) the next day. This looks the same as if the central bank made overnight loans TO member banks.

Draining surplus funds from the banking system

While repos and reverse repos are how the central bank makes day-to-day adjustments to the level of reserves, sometimes they feel the need to add to, or subtract from, the aggregate money supply in a larger way.

This is done through the selling of Treasury securities to banks (which drains reserves from the system), or the buying of Treasury securities from banks (which adds them).

This is initiated by the treasury but has an enormous impact on the level of banking reserves, so it must be coordinated very carefully with the central bank.

What is Quantitative Easing (QE)

Quantitative easing makes the overnight repo and reverse repo markets irrelevant. It basically causes these markets to cease to exist.

This is done via the central bank engaging in large-scale direct purchases of government bonds and possibly private securities as well.

The purpose of this is to flood the banking system with reserves.

By doing this, the actual interest rate is reduced to the floor rate (which is described above).

As regards government securities, it’s an asset swap. It’s providing money in exchange for treasury securities. Both of which are government-issued financial assets, of different types.

These government bonds (one asset type) are paid for with banking system reserves (the other asset type).

QE can lead to negative interest rates

While negative interest rates can at first seem like a bizarre concept, all it means is that rather than the central bank paying interest to member banks for the reserve balances they have on deposit at the central bank, they charge them a “storage fee”.

Why do negative interest rates even exist?

Why would a central bank do this?

Because they want the member banks to reduce their reserve rations, which banks do by making loans.

When a commercial bank has more loans outstanding relative to a specific amount of reserve balances, their reserve ratio, or the ratio of reserves to loans outstanding, is lower.

“Paying” negative interest rates (or charging reserve balance storage fees) is an effort by the central banks to nudge the commercial banks into making more loans.

However, loans are not something you can force on people, so this doesn’t always work

In order to make loans, there must be a demand for loans. And if there isn’t sufficient demand, no amount of negative interest rates is going to change that.

Why does the central bank set and manage to a target interest rate?

The goal of managing to a target interest rate is to maintain the Consumer Price Index at an inflation rate of 2%.

The purpose of this in turn is to encourage not putting off big-ticket purchases. If that new washing machine, or that new car, or that new whatever costs 2% more every year, the longer you put off buying it, the more it costs.

An inflation rate encourages people to NOT put off these purchases, for this reason.

Having said all that, there is no evidence that managing to a target interest rate helps with hitting a target inflation rate.

Monetary policy vs fiscal policy

Monetary policy is managing to a target interest rate.

Fiscal policy is how much the government is in deficit or surplus.

Monetary policy is a very poor means of managing an economy, in spite of the fact that there exists a widely held narrative is that it works. The evidence indicates that it doesn’t.

What DOES manage economies (for both good and bad) is the amount of deficit (or surplus) spending that is done by the government budget, as that changes the net money supply, also known as the supply of net financial assets to the private sector.

And… federal (currency issuer) surplusses destroy money

Literally.

It removes net financial assets of the private sector from the economy.

Why issue federal debt (sell treasury bonds) at all?

It’s not to pay for things. When the treasury borrows from the central bank, they’re borrowing money they previously created. Since they can create money when and as needed, why would they ever need to borrow it?

To help the central bank hit the target rate for overnight loans? If we let reserves in the banking system increase, the official interest rate will change to whatever the central bank pays on bank balances.

To provide safe assets to savers? Why not allow everybody to hold term deposits at the central bank? That would be much simpler.

Because there was once a reason, and we keep doing it because we always have? Actually, there once WAS a reason, back when gold was the only form of “real” money and exchange rates were fixed. But there is no reason to continue this practice today.

Professor Hail thinks this is one of those things that we do because we always have.

What if we stopped issuing government debt (selling treasury securities)?

Currency issuer fiscal deficits would add to “the net money supply” like they do now, but we would be leaving additional reserves in the banking system.

The official interest rate would be the floor rate, as it is under QE.

It would change only the way we talk about things. From a fiscal perspective, nothing would change, but that the currency-issuing government can never run out of money would be part of our discourse.

Rather than talking about how to balance the budget, we would be talking about how to balance the economy.

What he feels the central bank and treasury ought to do

Focus on balancing the economy, not the budget.

The currency issuer fiscal deficits should be enough, but not too much. If it’s too little, economic growth is constrained. If it’s too much, the economy experiences inflation.

Redefine the overnight interest rate as the rate paid by the central bank on reserve balances.

Continue to spend by keystrokes, as is done now, but leave the additional electronic currency in the system.

Offer term deposits at the central bank to savers.

Talk about the “net money supply” rather than the national debt.

But mostly, start talking about what it means to balance the economy, rather than the budget.