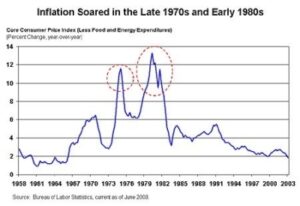

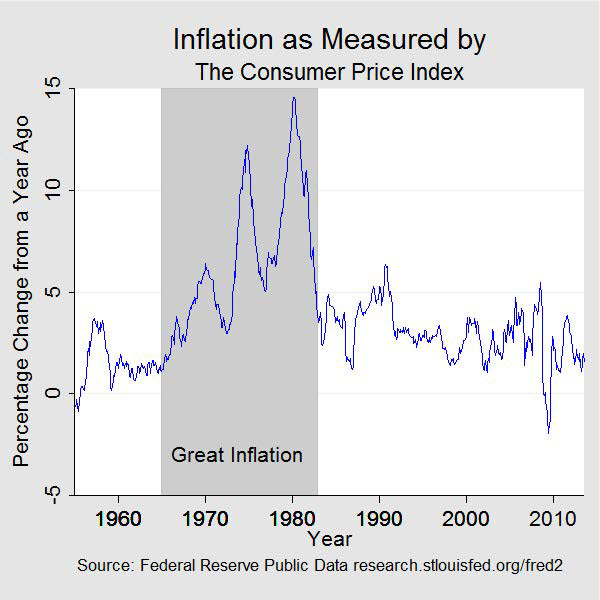

The great inflation of the 1970s actually started around 1965 as the chart below shows.

And believe it or not, the consensus on what caused it is not as strong as I used to think. Of all the economic and banking topics I’ve researched so far, I’ve found more papers on this topic than any other, but it seems to me the cause of this inflation must lie somewhere between “we’re not really sure” and “it’s complicated”.

You’re probably aware of the “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” quote made famous by Milton Friedman that a lot of people to this day buy into, but even Friedman himself later observed that in diagnosing the problem of inflation…

many factors other than money that politicians, economists and journalists write about… [They] attribut[e] the acceleration of inflation to special events—bad weather, food shortages, labor-union intransigence, corporate greed, the OPEC cartel…

Nelson, Edward. “The Great Inflation of the Seventies: What Really Happened?” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2004, p. 2. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.762602.

Below is a list of the studies I reviewed before writing this post, along with a summary of their ideas about what caused the great inflation of the 1970s.

————————————

This post is part of a larger series and sub-series.

Here is a link to the series: The history of banks and banking regulation

and to the sub-series: United States Banking and Bank Regulation History

————————————

Table of Contents

THE GREAT INFLATION OF THE 1970s

The overall conclusion is the Federal Reserve did not respond to 1970s inflation developments strongly enough, that is they did not raise interest rates fast enough, but they state the reason why is not clear.

However, they do comment that a severe and persistent reduction in the economic growth contributed.

The Great Inflation: The Rebirth of Modern Central Banking

This study comments that inflation, including the two spikes of the mid 1970s and around 1980 occurred in all the G7 nations at the same time, but the levels of inflation did differ from country to country.

Additionally, this inflation was accompanied by increases in unemployment and a notable slowdown in growth.

I think the most significant sentences from this study are:

Price changes arise from imbalances in demand and supply and either supply or demand shocks can have influence. In the aggregate, inflation could arise from either source. Identifying the relative importance of “demand” and “supply” shocks as drivers of inflationary developments is a perennial issue, and, unsurprisingly, a matter of controversy with regard to the Great Inflation. In the post–World War II era, including during the Great Inflation, the identification of “cost push” versus “demand pull” inflation occupied many discussions but perceptions varied with schools of thought. Among the economists identified as “monetarists,” over expansionary monetary conditions and excessive nominal aggregate demand, virtually axiomatically, were given prominence in explaining inflation outcomes. Among those identified as “Keynesians,” the adverse inflationary outcomes were more often than not identified as due to adverse supply.

They further state that the energy price increase from the 1973 oil embargo and agricultural shortages due to unusual weather contributed.

The Great Inflation of the Seventies: What Really Happened?

The very first paragraph of the introduction opens with “Across all explanations, there is important common ground: monetary policy was, in retrospect, too expansionary in the 1970s, and a tighter monetary policy would have been required to produce lower growth in nominal aggregate demand and, hence, lower inflation.”.

However, they do later claim the Fed chairman in 1973, Arthur Burns, wrote of “critical shortages of basic materials” and that “fuel prices spurted upward”, which seem inconsistent with the opening presupposition.

The Great Inflation of the 1970s

This is a very technical paper filled with equations and description of models, and closes with the following sentences.

We interpret the essence of what happened as follows. A rise in expected inflation occurred, perhaps in conjunction with a bad technology shock (e.g, the harvest failures and oil embargo). The Fed responded by raising interest rates. However, they did not raise rates much in relation to the actual rise in inflation. They clearly understood that higher rates would have stopped the inflation, but they did not resort to them because they feared what that would do to the real economy.

The real economy responded to these events by falling into a severe recession.

In short, shortages contributed (harvest failures, oil embargo), loose monetary policy contributed, and the “fix” such as it was, was to raise interest rates enough to diminish demand enough to induce a recession.

The Great Inflation and Early Disinflation in Japan and Germany

The opening of this paper presupposes that Japan and Germany had lower inflation due to “strong discipline on the part of Japan and Germany’s monetary authorities – e.g., more willingness to accept temporary unemployment, or greater determination not to monetize government deficits.”.

I find myself getting leery when the pre introduction (literally the paragraph before the introduction section) presupposes the conclusion, in advance of any supporting data being provided.

Later is this study, the author states “The belief in policy circles that inflation is very costly to the economy and, therefore, to society does not distinguish Germany and Japan in the 1970s from countries like the United States and the United Kingdom. Rather, the resistance to nonmonetary views of inflation is what makes these countries unusual.”.

These sentences also presuppose inflation to be solely monetary phenomenon.

In fact, the entire paper argues that the Monetary-Policy-Neglect Hypothesis was THE source of inflation, and Germany and Japan did less neglecting. This idea is supported in the conclusion where the author concludes what he previously presupposed to be true.

This paper makes no mention of shortages.

On what do these five papers agree?

They all focus on monetary policy (central bank interest rates) as at the very least a contributing factor, while four of the five made mention of shortages being an contributing or preceding factor.

All agree that to curb inflation central bank interest rates needed to be raised faster, and the reason for this was to dampen demand.

Four of the five studies state or imply that the reason we needed to dampen demand was shortages.

So, do we have a definitive answer? It would appear the answer to that is “It depends”. To a fan of “inflation is always a monetary phenomenon”, the answer might be yes, although I personally find it interesting that four of the five papers do make references to shortages.

To me, a non economist, the idea that shortages either contribute to or preceded inflation seems rather sensible. Almost intuitive. As one of the primary ideas in (I believe) all economic schools of thought is the idea that pricing is a function of supply and demand.

It seems to me, again as a non economist, that the answer to what causes inflation lies somewhere between “We’re not really sure” to “It’s complicated”.