Yet these economic ideas are still used as the basis for public policy.

This blog post identifies some and clarifies how we know they’re false.

This post is also part of a larger extended series of blog posts on banks and banking regulations, the lead post of which can be found via the link earlier in this sentence.

We know these economic ideas to be false, yet…

Economies are the aggregate of “rational agents” making decisions

The rationality postulate figures in every neoclassical economics model. The idea is that we make the best decision possible, to further our own interests, with the information we have available to us.

This means acting with good reasons, with as much information as we have access to, for our desired outcomes.

The problem is, in 2017, Richard Thaler was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Science for his work in integrating economics with psychology, where he demonstrated that people make economic decisions based on “limited rationality”.

This idea is something we know to not be true, yet economists still assume it is true and use it in their models and when drafting public policy.

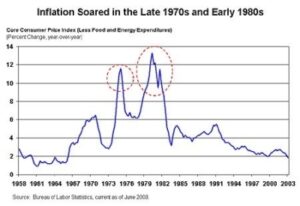

There is a Non Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment

This is called the NAIRU. The idea is that if unemployment drops too low, inflation is inevitable, is created as a result of unemployment being too low.

How do we know it’s not true? By watching inflation since the mid-1980s and observing that this just isn’t true.

As explained in this paper: Time to Ditch the NAIRU.

But like other zombie ideas, it just doesn’t want to die.

National treasuries borrow from national central banks

When the central bank creates new money, out of thin air, that the national treasury then borrows, who are they borrowing from?

Perhaps the question is better stated if government department A (the central bank) creates money and deposits it into the account of government department B (the treasury), why do we call it borrowing?

Both the central bank and the treasury are part of the same government, and yes, I know central banks are this weird hybrid of a government agency that is owned by banks, and there is an idea that central banks are independent, but central bank independence is what the national legislatures say so in the laws governing the operation of the central bank. In this regard, they’re no different from any other government agency.

So when national treasuries borrow from national central banks, the nation creates money it then loans to itself.

This is as if my right pocket loaned money to my left pocket. I’m making the loan to myself.

Yet the language we use around this implies that currency-issuing governments do in fact borrow the currency they issue, which they don’t.

Banks loan out deposits and are financial intermediaries

Humans have been banking now for about 5,000 years, and there are still competing ideas of how banks fund bank loans. People believe ideas about where banks get the money without actually bothering to find out. Which is weird.

Finally, in 2014, a Professor of Banking and Finance named Richard A. Werner ran an experiment to find out. Which should bring this discussion to and end, but doesn’t.

There is an idea floating around that banks are financial intermediaries. That banks get money from depositors and loan it out to borrowers. We now definitively know this idea is false.

There is another idea of “fractional reserve banking”, where new money is created within the banking system, and the ability of an individual bank to loan out money depends on the amount of reserves they have on deposits. We now definitively know this idea is false.

The final idea, what we now definitively know to be the correct idea, is that banks create money out of thin air when they make loans, without caring if they have sufficient reserves to support that loan, then they borrow needed reserves (from the central bank) after the fact to keep the reserve ratio in line with whatever banking regulation they need to meet.

So while it’s kind of wild to think that commercial banks create money out of thin air every time they loan out money, that is in fact what happens. The money doesn’t “come from” anywhere. It just “magically” appears in a deposit account which is made available to the borrower.

And many economists don’t seem to know this.