If you found this post via search, it probably makes sense to start with the first post in this series on the cost of shipping. The link to the full series is above, and here.

Table of Contents

Is the bigness of modern ships because of anticipation of a never ending shipping boom as we saw prior to the great financial crisis?

The slump in the growth of trade wasn’t the only factor here.

Ship lines, like companies in many other industries, have relentlessly pursued economies of scale.

Bigger was better.

And that WAS true when you could build a ship that could carry three thousand containers instead of two thousand containers.

The cost per container dropped a lot.

When they built ships that could carry ten thousand containers vs five thousand containers, the cost per container became lower still.

So ship lines were aggressively pursuing economies of scale.

What they didn’t count on was that at some point the vessels would get so big that diseconomies of scale would set in.

And that’s what’s happening in shipping now.

As ships got beyond perhaps seventeen or eighteen thousand TEUs, they just got too big.

And that’s when you started to have this confusion in the ports, when you started to have these delays in shipping, and when the entire industry become less reliable.

And the diminished reliability in the shipping industry is leading manufacturers and retailers to change their sourcing patterns.

To make their products in different places and to have different value chains.

Size isn’t everything, and many of the ship lines mistakenly thought that it was.

Is there any other key idea we’re missing that would help us understand the current situation?

There is a lot of concern now about shortages of containers, and shortages of chassis [intermodal chassis are the frames the containers fit into which are hauled behind trucks – the image below is an empty chassis being towed behind a truck].

Part of this is that the ship lines have gotten out of that business and left it to other people.

International trade, after all these years, still doesn’t work very smoothly.

There are still lots and lots of manual steps involved in arranging shipments.

There are lots of unexpected delays, and this situation really hasn’t gotten better in recent years.

What happens in a system like we’ve got in shipping, is that ship lines built ships that they thought were best for their own needs.

They didn’t really give much consideration to other participants in the system.

And the system includes the containers, the terminals in the ports, the ports themselves, the railroads that pick up and deliver to the ports, the truck lines that pick up and deliver to the ports, the companies that provide containers, and the companies that provide the chassis the trucks pull.

All of those folks are players in this ecosystem.

And the giant ships that were most efficient for the ship lines alone, haven’t been most efficient for the whole system.

It’s really made it less efficient over time.

How long does it take a ship to travel from Shanghai to Los Angeles?

These days it takes somewhere around sixteen or seventeen days.

It actually takes a couple of days longer than it did twenty years ago.

This is because the price of fuel is one of the most expensive costs in shipping.

Initially, the ship lines slowed down their vessels when the price of fuel went up. This was called “slow steaming“.

The idea is that they would operate more slowly to hold down the total cost of fuel.

Then newer generations of vessels were built, like these ships that carry almost 24 thousand TEUs, to steam slowly.

They can’t speed up.

And one of the reasons for current delays is that it’s harder now than it used to be for a ship to make up time.

It used to be that a ship would sail at an average of 21 knots, but if it got behind it could steam at 24 knots for a while, to get back on schedule.

The ships can’t do that anymore. They’re typically sailing at 17 knots and they can’t go much faster than that.

Once they’re behind, they’re behind.

Is there anything we missed?

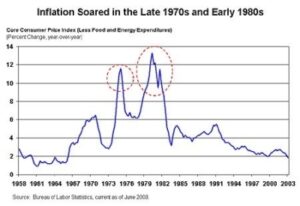

One thing that hasn’t come to the fore yet, as interest rates are very low, is that this global shipping slowdown will drive up inventory costs.

Think about the time goods spend on a ship. While they’re on the ship, the goods are inventory.

If it’s taking three days longer to ship stuff, inventory costs are effectively higher.

Right now, with very low-interest rates, this isn’t a big deal, but if interest rates become significant again, this will be a cost burden.