Disclaimer: I’m learning, so while I strive for accuracy, I’m open to the idea that I don’t fully understand what this international organization does, or how it operates. This is especially true as the International Monetary Fund is in some ways like a bank, and in other ways not like a bank.

Table of Contents

Is the International Monetary Fund a bank?

They’re kind of really more like a credit union, where money is pooled together, then loaned out.

They do make loans, which need to be repaid, and those loan agreements come with strings attached, which go beyond the “mere” repayment of the loan.

Their criteria for making loans is based on the creditor nations making changes based on “moral judgments” banks typically do not concern themselves with.

And, the changes mentioned above require structural reforms to the laws of a debtor country, in the areas of private property, and access to resources.

What does the International Monetary Fund do?

They appear to do two primary things, surveillance, and lending.

Surveillance

While the name surveillance feels a bit ominous after the Edward Snowden and Katherine Gunn revelations of government surveillance of our electronic communications, in the context of the International Monetary Fund it means monitoring the economic policies of its member nations.

So, maybe not quite as ominous.

The idea is to identify potential risks to stability and to recommend appropriate policy adjustments needed.

Lending

This lending is for countries that need money to maintain their balance of trade, primarily it seems because they are net importers, which of course requires a net outflow of money.

The lending is to support their ability to import needed stuff after some crisis occurs, be it an extreme weather event that destroys domestic food production, political corruption, war, etc.

There is one quote on the IMF web pate about this that I do find particularly interesting:

“…to create breathing room as they implement adjustment policies to restore economic stability and growth”.

The IMF has a set of policies they require debtor nations to adopt, and if you want the loan, you adopt the policies.

The strings the IMF attaches to loans

The IMF calls them Structural Adjustment Programs or SAPs.

If you want an IMF loan, you MUST:

- Allow foreign investors to buy rights to mineral deposits and other resources within your country.

- Privitize public enterprises (which could be an oil company, or could be a transit system).

- Reduce expenses for social services.

Critics of these IMF requirements say the IMF is actually making the gap between the rich countries and the poor countries wider, and they’re doing so on behalf of multinational corporations who want access to the in-country resources.

What currency or currencies does the IMF lend in?

To me, this part is super interesting.

As the IMF consists of 190 member nations and seems to have loans outstanding with 79 counties right now, do they make loans in “local” currencies?

No.

Special Drawing Rights

Special Drawing Rights seem to be the IMF “currency” that they very clearly claim is not a currency.

The SDR serves as the unit of account of the IMF and other international organizations.

The SDR is neither a currency nor a claim on the IMF. Rather, it is a potential claim on the freely usable currencies of IMF members. SDRs can be exchanged for these currencies.

Unit of account means all IMF loans are denominated in SDRs.

And “is a potential claim” means the holder of SDRs can claim or demand some other currency in exchange for the SDRs they’re holding.

So, what is an SDR?

It’s a “unit of account” whose value is determined by rules defined by the IMF.

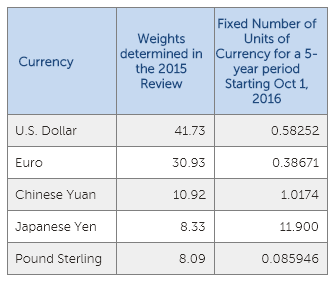

An SDR is made up of a set of national currencies. The value of an SDR is determined by the values of the currencies included. The composition of the component currencies is reviewed and adjusted every 5 years.

Here is the current makeup:

How does a debtor pay back SDRs?

Believe it or not, I could not find an answer to this question.

It seems reasonable to believe that if they are loaned SDRs they then have to pay back SDRs, but of course, they don’t buy stuff in SDRs, so SDRs must be converted to, and from, other currencies.

I emailed this question to an economist who used to work at the IMF and if I get an answer I’ll share it here.

Having said that, here is what I found on Investopedia…

The IMF member states that hold SDRs can exchange them for freely usable currencies by either agreeing among themselves to voluntary swaps or by the IMF instructing countries with stronger economies or larger foreign currency reserves to buy SDRs from the less-endowed members.

International Monetary Fund. “Special Drawing Right (SDR) Allocations: What happens to the SDRs once they are allocated?” Accessed Oct. 4, 2020.

So it appears that once an IMF debtor receives SDRs, they convert them into other currencies in order to buy stuff, and when they need to make a payment to the IMF they must obtain SDRs in order to do so.

Having said that, I hope the economist I emailed my question to gets back to me.

Where does money the IMF loans out come from?

Unlike commercial banks who quite literally create money as loans are made, the IMF seems to create a pool of money which they collect from member nations, and this is the money they loan out in the form of SDRs.

IMF member nations have quotas, which are based on the relative position of the member nation within the global economy.

The richer you are, the more you kick in, but the more say you have in IMF operations as a result.

When the IMF boards and committees meet, it’s not one vote per person.

Votes are weighted by the quota of the country the representative represents.

A member country’s quota determines its maximum financial commitment to the IMF, its voting power, and has a bearing on its access to IMF financing.

International Monetary Fund Factsheet

How big is the IMF pool of money?

Not nearly as much as I imagined.

Their current total resources are SDR 973 billion, of which SDR 707 billion are currently loaned out.

Right now, one SDR converts to USD $1.42, so expressed in USD…

- Total IMF resources: USD $1.38 trillion

- Total IMF loans outstanding: USD $1 trillion

When you consider that the USA and the European Union spent more than that on their stimulus packages, the IMF pool seems small, considering its global reach.