Financing world war one started simply, as people expected the war to be quick. As months dragged on, things got more complex.

The United States was neutral during the first two years of the war, from 1914 to 1916, and during that time provided supplies to European nations through the neutral country of Sweden. These supplies went mostly to Britain and her allies, which the Germans did not appreciate. Germany then extended its shipping blockade of Europe to include neutral countries, including Sweden and started destroying American merchant vessels through submarine attacks.

This led the United States to declare war on Germany which occurred on April 4, 1917.

————————————

This post is part of a larger series and sub-series.

Here is a link to the series: The history of banks and banking regulation

and to the sub-series: United States Banking and Bank Regulation History

————————————

When Britain declared war on Germany in August of 1914, Britain and the US decided they needed their currencies to retain parity with each other, so both nations decided to stay on the gold standard. At the time London was the center of the global financial system and the architect of the gold standard.

Since staying on the gold standard limited the amount of money in the American economy, the United States had to raise money to fund the war, which they did through taxes, borrowing, and “money printing” through the selling of Treasury Securities through the newly created Federal Reserve.

Taxes raised about one-fourth of the US actual war expenses as well as helped remove money from the economy which damped demand for goods and services just when the government was increasing competition for those resources by mobilizing for war.

But borrowing was the main source of paying for WW1, which fell into two broad categories: money borrowed from the central bank and private banks, and war bonds sold (as Victory Bonds) to anyone who wanted one.

Banks provided more short-term loans, and war bonds provided more long-term loans.

Between 1914 and 1918, the total borrowing taken out by the Entente (the countries at war with Germany) was about $16 billion, which was an enormous sum at that time.

US banks were the largest creditors, lending $7 billion. $3.7 billion went to Britain, $1.9 billion went to France, and $1 billion went to Italy.

British banks loaned out $6.7 billion, and French banks loaned out $2.2 billion. Britain and France were simultaneously big lenders and big borrowers.

By the time WW1 broke out, the liquidity and reach of private banks had outstripped the ability of the nation-states to regulate them. For communists like Lenin, this demonstrated that capitalism had entered an imperialism stage. But no matter, within the Entente nations, nations turned to private banks for financing.

JP Morgan specifically did a lot of business with European nations (England, France, and Russia) by representing them in their desire to borrow from New York banks. This earned them commissions of 8.3 percent, for total profits of $200 million.

Washington could have made this illegal, but instead kept an eye on the lending relationships. There was tension between the Wilson Administration and the Federal Reserve over how much US banks should lend, or should be allowed to lend.

The Fed chairman (Benjamin Strong) was a supporter of these loans and President Wilson saw withholding credit as a means to discipline what he saw as intra-European imperial recklessness, and hopefully force them into a negotiated peace.

In November of 1916, Wilson ordered the Fed to instruct American banks and investors to stop foreign currency loans and purchases of foreign securities, a move that almost stopped the financing of the war for the Entente nations.

This positioned the United States to be the undisputed economic leader in the event the United States entered the war, which it did five months later.

The financing of WW1 had the effect of putting big business front and center as regards war mobilization. The big loans were made to big banks who in turn made loans to big businesses who in turn provided governments with the goods and services needed to wage the war.

This had the effort of financially rewarding the owners of these big businesses while the average citizen was suffering, both physically and financially. The war was very lucrative for a small handful of people involved in providing armaments, vehicles, airplanes, fuel, etc while devastating European populations.

It’s no wonder some people were characterized as “war profiteers”. Especially considering that after the few profited enormously, the nations taxed their firms and citizens so they could make good on their loan payments.

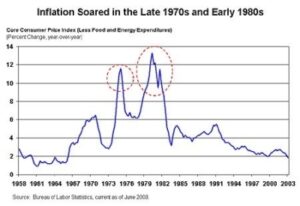

As war has a way of damaging production capacity while simultaneously creating demand, the first world war created a global rise in prices. From 1914 to 1918, the average price level in countries directly involved in the war doubled. 196% in Japan, 203% in the USA, 235% in Great Britain, 217% in Germany (soon to cascade into hyperinflation), 340% in France, and 409% in Italy.

Because European colonial powers controlled the currency and securities circulating in their colonial economies, the deficit financing of the European nations contributed to inflation throughout their colonial empires. This inflation fueled social unrest and anti-colonial uprisings.

In Europe urban-rural connections were breaking down, causing food shortages in the urban centers. In Asia, a rice crisis would last three years after the war ended.

The economic result was a sharp global recession from 1920 to 1921, which added fuel to the fire of anti-colonial protests and crackdowns.

In four years of war, three European nations (Britain, France, and Germany) collectively destroyed $12 billion of foreign assets, which was about a third of the total foreign assets built up during the 19th century.

This started the decline of London as the center of the financial world and the elevation of New York.

Financial centers in neutral European nations (Amsterdam, Zurich, and Stockholm) benefitted financially from the financial harm inflicted on the larger nations surrounding them.

They became sources of capital for reconstruction, and during the 1920s outperformed British, French, and German banks still working to regain their pre-war positions.

Restrictions on the ability of European banks to finance operations around the world led to lower levels of investment in infrastructure in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and East Asia.

This led to slower growth in these regions and a growing dependence on the United States, and an outright Americanization of Latin America.

The war debts also positioned the United States (or more specifically its banks, which the government was able to use for geopolitical purposes) as the chief creditor to the world. European nations were a bit dismayed that American banks demanded fairly rigid repayment schedules, which stretched European resources thin as debt payment and reconstruction projects had to occur at the same time.

For the various reasons above, WW1 lifted the United States into the dominant geopolitical position it has occupied ever since.