When the American colonies were British, each colony issued their own currency, denominated in the British currency units: pounds, shillings, and pence.

The values of each currency varied between colonies. A pound issued in Massachusetts for example was not equivalent to a pound issued in New York.

————————————

This post is part of a larger series and sub-series.

Here is a link to the series: The history of banks and banking regulation

and to the sub-series: United States Banking and Bank Regulation History

————————————

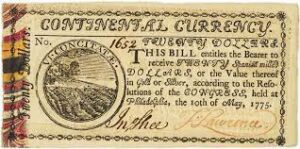

When the American War of Independence started in 1775, the Continental Congress, needing a way to buy stuff for the war effort, started issuing paper money, Continental currency, commonly called Continentals. This was full fiat currency, not backed by any commodity such as gold or silver.

The American colonies had a successful experience of issuing such fiat currency during the earlier French and Indian War. It was however considered, perhaps with hindsight, that the success of the currency during the prior war was due to a government (the British) limiting the quantity of currency issued, and replacing it with “better” currency after the war ended.

Continental currency was denominated in various values from $1/6 (16.7 cents) up to $60.

This continental currency was valued per the colonies/states currencies at various rates:

- New Hampshire: $1 = 6 shillings

- Massachusetts: $1 = 6 shillings

- Rhode Island: $1 = 6 shillings

- Connecticut: $1 = 6 shillings

- New York: $1 = 8 shillings

- New Jersey: $1 = 7 1/2 shillings

- Pennsylvania: $1 = 7 1/2 shillings

- Delaware: $1 = 7 1/2 shillings

- Maryland: $1 = 7 1/2 shillings

- Virginia: $1 = 6 shillings

- North Carolina: $1 = 8 shillings

- South Carolina: $1 = 32 1/2 shillings

- Georgia: $1 = 5 shillings

Congress was in a bind because while they needed to buy stuff for the war effort, the Article of Confederation had not yet been ratified, so in 1775 Congress was, legally, a forum for consultation among sovereign allies.

Congress adopted the Articles of Confederation on 15 November 1777, and they were ratified on 1 March 1781, at which time the United States came into existence.

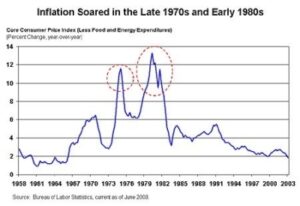

This whole currency system was new, there was a war on, and Congress and the states coordinated badly about how much currency should be issued.

Congress and the states issued much more currency than there were goods and services to buy (the productive capacity of the colonies could not produce enough to meet demand which all that currency influenced – after all, there was a war on), and the British waged a form of economic warfare by large-scale counterfeiting of Continentals, using bills that were so well counterfeited that before the Americans figured it out, immense quantities of these counterfeit bills were circulating throughout the colonies.

This caused the value of the Continentals to plummet during the course of the war. By 1778 Continentals were worth 1/5 to 1/7 of their face value. By 1780, they were worth 1/40th.

By May of 1781, their value was so badly reduced that people stopped using them.

After the collapse of the Continental currency, Congress appointed a Superintendent of Finance of the United States. A man named Robert Morris.

Morris advocated for the creation of an American bank, the first American financial institution, the Bank of North America, which was chartered in 1782.

To prevent a reoccurrence of the runaway inflation of the Continental currency, a provision was inserted into the Constitution preventing states from issuing currency, except for gold and silver coin.

No State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation; grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal; coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts; pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts, or grant any Title of Nobility.

US Constitution, Article I, Section 10, Clause 1